The resounding success of the Sapphires seems a significant moment in Australian culture. The film has not only been a popular hit with mainstream audiences, it has also received the top AACTA awards in the industry, winning best film, director and female actor. This energetic comic tale is seen as a ‘positive indigenous story’, by contrast to the hard truths of films such as Samson & Delilah. I certainly enjoyed the powerful Deborah Mailman, the enlivening Irish manager, the pumping soul music and even the inventive editing. As the writer Tony Briggs said, 'I wanted this film to be more about fun and entertainment than anything else'. Enough said?

But reality is hard to hide. The premise was about a group of Aboriginal singers going to Vietnam to entertain US troops. Despite the now conventional view that this war was a heroic struggle of independence by a small nation against a more powerful aggressor, The Sapphires sidesteps the moral context of the war. In terms of the narrative, the only issue at stake is the capacity to put on a good show for the invading army. The reality was quite different. In the real story, only two Sapphires went to Vietnam. The others stayed at home because they were part of the Australian anti-War movement. Why has this been deliberately overlooked in the film version?

As a comic film, it’s understandable that it uses simplifications in order to heighten emotions: all white Australians are prim racists and US popular culture promises liberation from prejudice. But the appeal of these stereotypes is limited to local audiences. The Sapphires had only a five week run in the UK, was called ‘le flop’ in France and received tepid US reviews. Why do Australian audiences enjoy this story so?

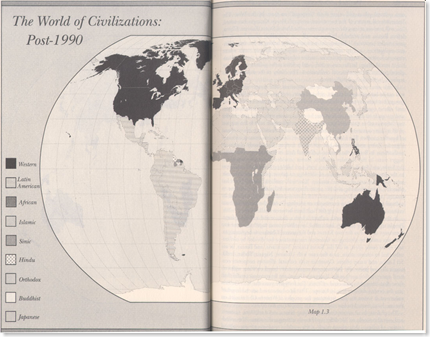

Maybe it's an essentially provincial story. It reflects an innocent and isolated settler colony nostalgic for the world once made familiar by a dominant Western power. This nostalgia emerges at a time of a quite profound political realignment of Indigenous and conservative voices.

Some Aboriginal voices now distance themselves from the liberal left. Marcia Langton’s Boyer Lectures have set the interests of the emerging Aboriginal middle class directly against the patronising southerners—‘leftists’—associated with the wilderness movement and social justice.

This divergence has been growing in recent times, in much less partisan ways, as Aboriginal interests engage with established power rather than be boxed into the radical margins. Figures like Tracey Moffatt embrace the global art scene in defiance of the perception that she should be earnestly depicting the plight of her people. Indigenous scholars such as Christian Thompson make the pilgrimage to Oxford. And in the academy, Indigenous Studies aspires to value of the sandstone university rather than identify with declining critical studies.

The trajectory of emancipation thus seems to lead away from the values of solidarity that set it in train. Isn't it the ultimate form of empowerment for an Aboriginal artist not to make work about Aboriginality? It's hard to question this form of success. Besides, the days of a non-indigenous person questioning Aboriginal choices has long gone.

So where does this place the southerner, who once saw solidarity in defending indigenous culture against the ravages of historic colonialism and mainstream capitalism. Is this just another sign of the liberal left’s growing irrelevance? Just as Western Sydney has deserted the ALP, and developing nations go for economic growth before environmental sustainability, are the ideals of the educated classes revealed as self-absorbed fantasies, designed more for ideological fashions than real action? Like Graham Greene’s deluded romantic heroes, are the champions of global change now lost in the real world of nations, each scrambling over each other to climb the ladder?

What do you say to someone from a 'developing' nation who baulks at energy limits, saying why should we have to pay for your mistakes? Why shouldn't we enjoy the same privileges as you take for granted?

Certainly, one path is to accept the seeming inevitable. I remember talking a white academic in South Africa about the fellow travellers who has been part of the freedom struggle, yet were completely ignored by the incoming ANC government. Those at odds with the government, like Coetzee, were seen as unable to accept that collective victory may come at a personal cost. It seemed an important part of the story of solidarity that even its heroes had to learn to step aside so that black empowerment could develop. As the professor said, ‘It’s what we all fought for after all.’

But while resentment should be avoided, does it follow that the original ideals must also be abandoned? To do so implies that the values originally espoused were dependent on validation from elsewhere—that ideals were upheld in the name of the other, not in their own right.

In the previous Arena, Boris Frankel wrote ‘Indigenous people can’t suddenly become mainstream and yet be exempted from the same obligations of non-Indigenous people to prevent dangerous climate change.’ Yes, but rather than couch this in moralistic terms, it seems more appropriate to place the onus on the settler position: non-indigenous should not lower their expectations of ethics dependent on indigeneity. Despite acknowledging the individual benefits of working in the mining industry, we should still expect Marcia Langton to mention the greater challenge of climate change.

There are significant Aboriginal voices that seek to articulate a common good. Christine Black's book of indigenous legal theory, The Land is the Source of the Law, offers a particularly strong Aboriginal context for environmental concerns in the thinking of Senior Law Men.

Across the Pacific, the buen vivir movement in Bolivia and Ecuador shows how a successful indigenous movement can emerge and still contest the mainstream. Even if such values do seem increasingly marginal, particularly with a three-term Liberal national government looming, they shouldn’t be abandoned. The historical commitment of Aboriginal leaders and communities to maintain an Indigenous culture, despite its status as ‘backward’, should be the very example that inspires an ethical stance today.

Marcia Langton’s Boyer lectures are a wakeup call. Arena demonstrates its relevance by offering a rare forum for debate on this issue, aided now by the Project Space which showed the paintings by Garawa man, Jacky Green, testifying to the destruction of sacred land by mining.

However, from Langton’s position, we ‘leftists’ reading Arena are in danger of being seen as just like those prim white Shepparton settlers in The Sapphires. Perhaps we are more likely to be cast in this role by rejecting mining outright, despite its obvious benefits for a large community of Australians. Sure, the obese extractocrats make it easy to pillory these ventures. But should Langton be the only outside interest at their table? Without being beholden to the mining industry for research funding, it should be possible to advocate for environmentally responsible practices.

So while it’s possible to enjoy the Sapphires, it’s also reasonable to feel that this leaves a story untold. Good morning Vietnam, g'day Ho Chi Minh City.

Thanks to Christine Black, Deborah Jordon, Damien Wright and Esther Lowe for feedback. A better version may end up in Arena Magazine.

![3518522464_e675d8d5ac[1] 3518522464_e675d8d5ac[1]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/__XVM4iCA-Ew/S8LaLrOXmSI/AAAAAAAAGIo/raNYZwk4X8s/3518522464_e675d8d5ac%5B1%5D%5B4%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)