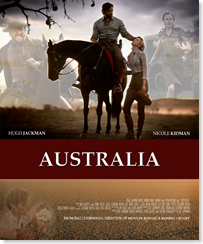

I spend most of my during Australia trying to counter my instinct to deconstruct its mythification. It seemed too easy to criticise the way it glossed over reality. Australia is, after all, an entertainment constructed to enchant the great southern land for a new generation. But there were two moments that left me feeling quite uneasy about the Australia that it constructed, particularly for a non-indigenous audience.

I spend most of my during Australia trying to counter my instinct to deconstruct its mythification. It seemed too easy to criticise the way it glossed over reality. Australia is, after all, an entertainment constructed to enchant the great southern land for a new generation. But there were two moments that left me feeling quite uneasy about the Australia that it constructed, particularly for a non-indigenous audience.

The plot of the film revolved largely around the plight of a young half-caste boy, Nulla. To a large degree, this was was the exclusive point of engagement with Aboriginal Australia. As such, it was a profoundly unequal relationship. While Nulla has a little magic at his disposal, he still needed the heroism of the Drover to save his life. The only reciprocal adult relationship was between the Drover and his ex-wife's brother, who taunted him that he didn't belong in this land. But the brother-in-law was removed from the plot, killed while valiantly defending the mission boys.

If I was a Freudian looking for an uncanny moment around while the film unravelled, then I would probably look to the scene when the Drover took charge of his promised stead, Capricornia. This horse differed from others primarily by its colour - jet black. The scene depicts the Drover manfully taming the wild energy of the horse, bringing it under his control and making it part of the business of the farm. It seems emblematic of what the film as a whole does, in subjugating the politically difficult indigenous cultures of Australia into a directorial spectacle. Why such a black horse? Why the absence of black men in the Australia that remained?

The second scene was at the very end. At first, I was relieved that Nulla was allowed to go walkabout with his grandfather. But the final words -- as I can remember them -- were along the lines of 'we are part of the same country, but you have your dreaming and I have mine.' So what did the film suggest was 'our' dreaming?

The overt non-indigenous myth in the film was the Wizard of Oz, which Nulla cleverly was able to elicit as a source of dreaming in the stiff English aristocrat. This choice of film was partly word play - on 'Oz' as the land of Australia and 'Somewhere over the Rainbow' as a reference to the rainbow serpent dreaming. But the Oz story itself reflected American cinema as a factory of dreams. As a product of this factory, Australia seemed more closely modelled on the American western than the tradition of local cinema. It had none of the eccentricity of the great Australian films of the 1970s. It was great to see an actor like Bruce Spence again, but he was left with a thinly stereotyped role, especially compared to the captivating appearance in Mad Max.

Apart from Hollywood as our dreamtime, the other major non-indigenous story was about the cattle industry. Surely at a time when we are more aware of the serious environmental degradation due to beef production, this seems hardly a pursuit on which to model Australia.

Maybe Australia is the last fruit of our spectacle culture. As financial realities knock down the economic house of cards, perhaps a new cinema will emerge to explore the cracks in the façade. After all, that's closer to home.